Miloš Petrović. Poetry.

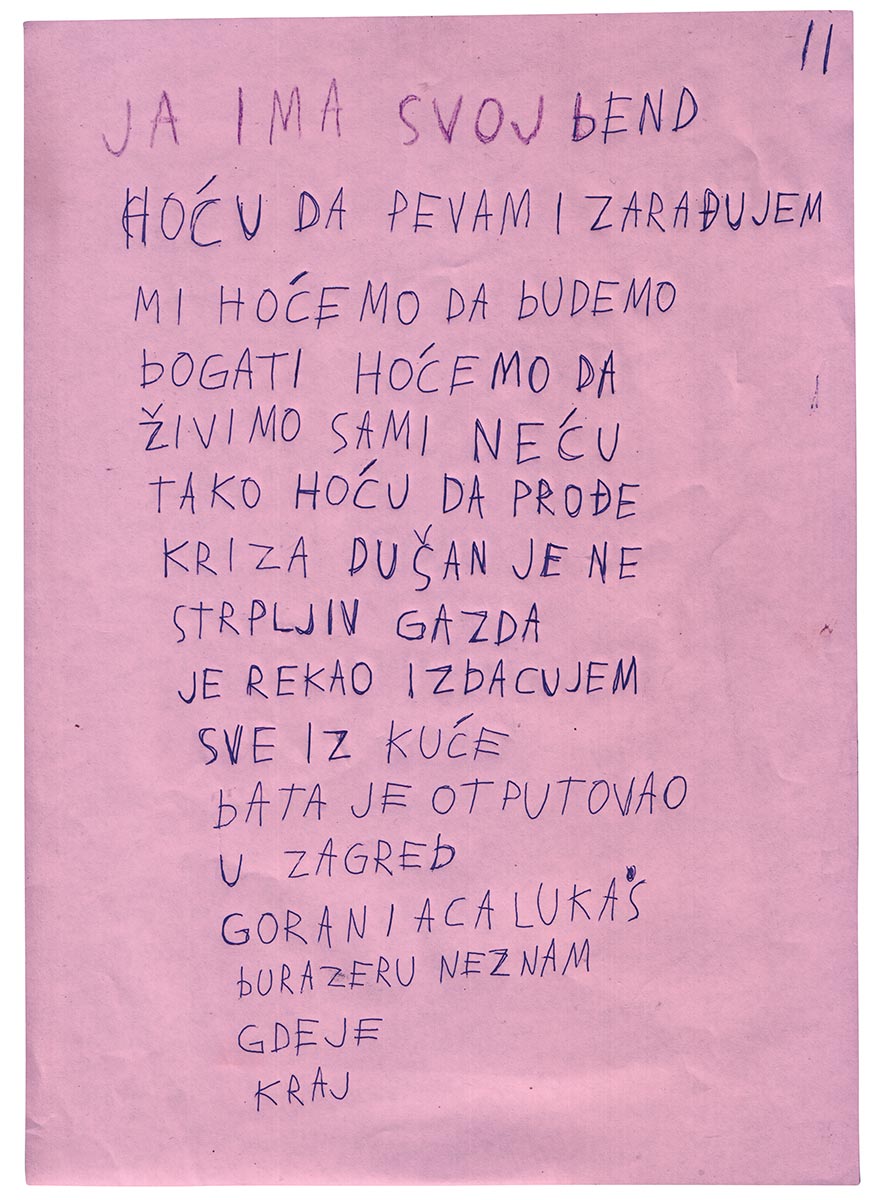

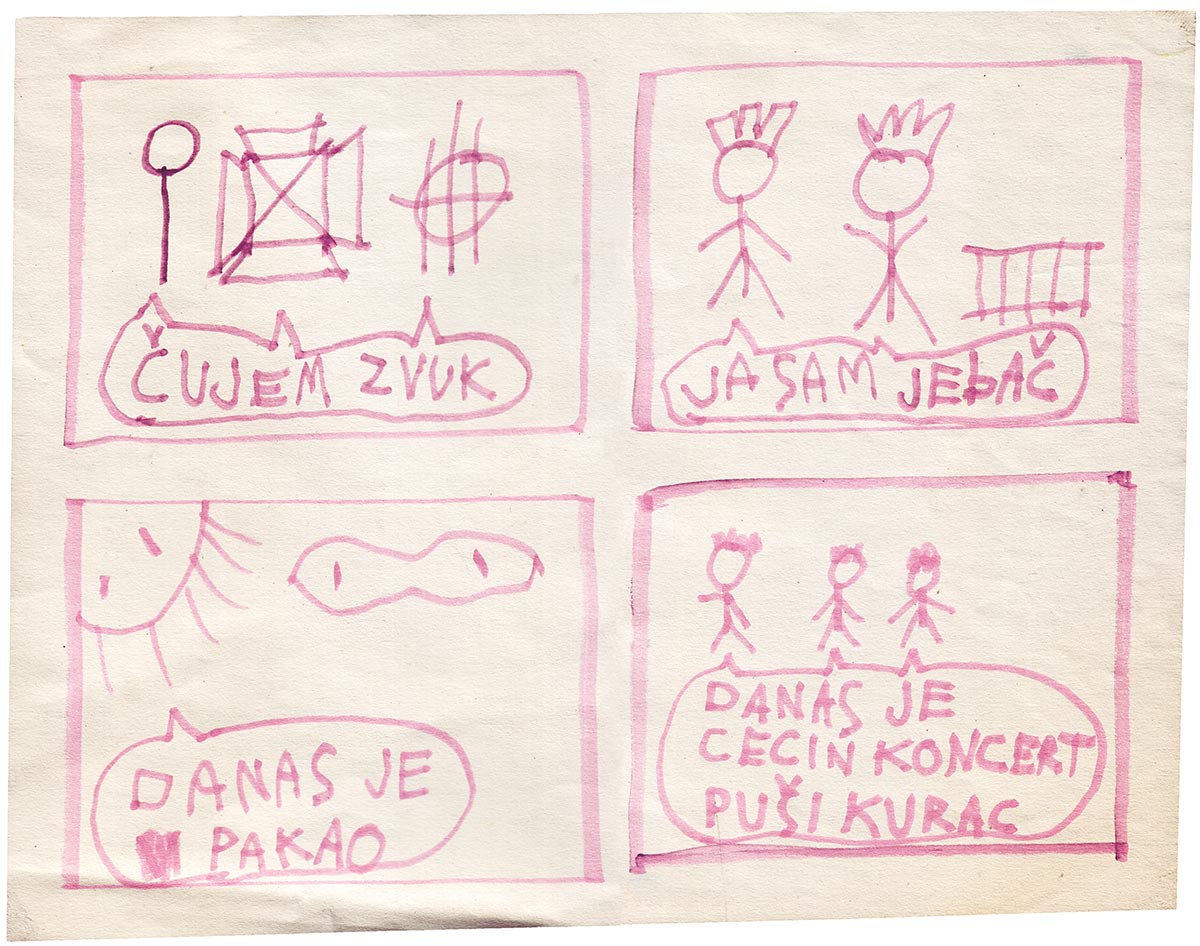

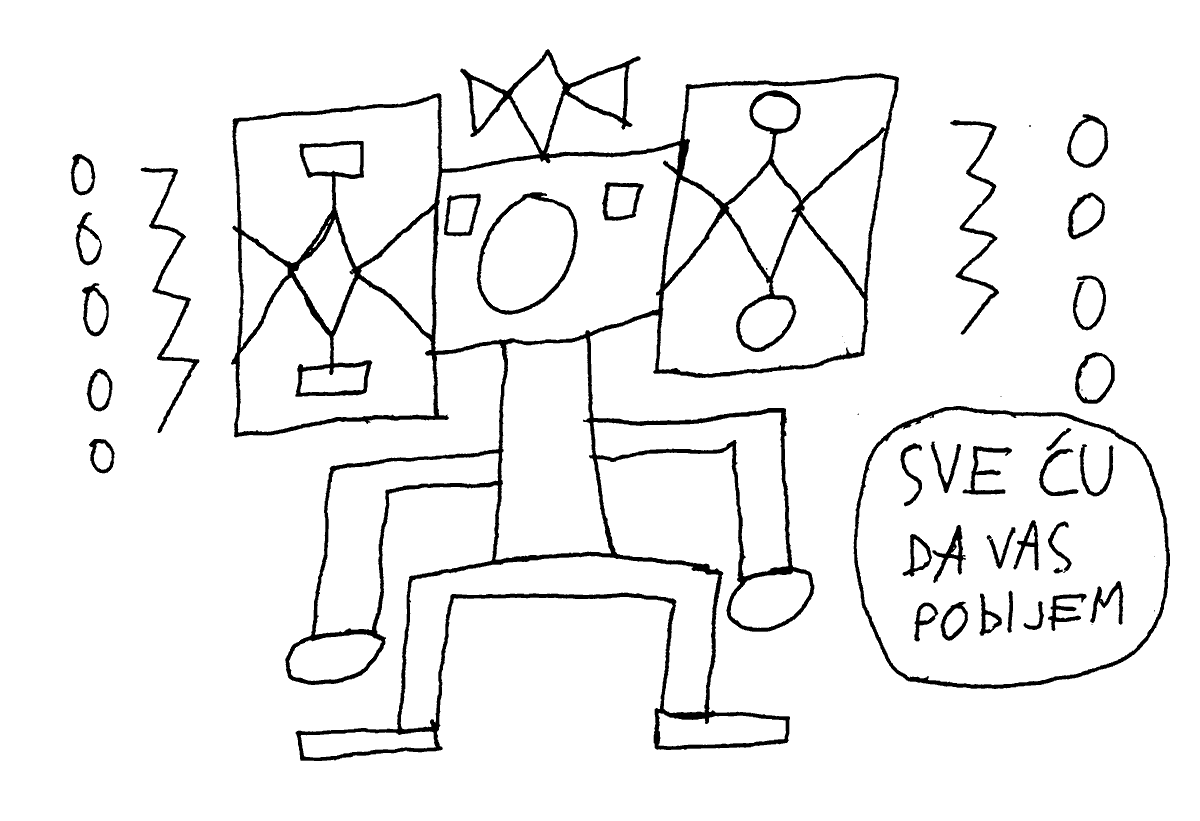

Miloš is, I would say, a street walker; or not. Maybe a fighter, but not a street fighter. His enemies are invisible to us mortals, his friends. His demons are clan leaders, corrupt policemen, power apes, educators, supervisors, in short, all those affecting his fate, which he has no effect on. He wants to get separated, from his family, his school, his community, all that which pisses him off. His strength, and his weakness, are his paintings, huge canvasses with seemingly simple and sparing brush strokes. Miloš is Africa. Miloš is from Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Miloš hates the colonizer, he recognizes him, and he is misunderstood. If he had things his way, none of us would ever worry. He needs money and he understands all too well how things work. And he hates, he hates all those invisible scoundrels, enforcers, he’s fighting snitches and pimps. The sense of justice is Miloš’s own sense. His justice is there among us all, he just goes and takes it out into the world. He has no problem starting a painting. He writes songs, names names, he is on the verge of excess, uncovering our little secrets in his grandiose verses, which are clean, purified, non-fat, essentially perfect. Secrets about us, which we are unaware of, are ours, yet we don’t know them, but he is here to tell us. It is impossible that all this is coincidental. There aren’t that many coincidences in a single place, in one verse. Sometimes he is very vulgar but he has no problem changing his behavior. He doesn’t repeat his mistakes, unless they are not mistakes. He is the authority, he chooses the mistakes. One mistake would be enough for him, but so far he didn’t have a crew. Now he has a crew, we all see each other on Tuesdays and Fridays, we are all slightly older, thus, these well-timed, rhythmical intervals between our meetings, and always difficult goodbyes, are well-suited for us. See you Tuesday is the saddest word in Matrijaršija. Miloš, Bata, Toni and Dule will go home on Friday night, when it’s the best, and spend Saturday, when it’s even better, and a devastating Sunday and Monday, as punishment. Because, all this time they would be waiting for Tuesday. And then others would tell them that they can’t go. No, you can’t go to Matrijaršija, Miloš, because, and I paraphrase and half quote this, you can’t go, Miloš, because you haven’t paid all your debts. You haven’t got enough money for cookies. Let alone chocolate. Miloš is looking at us, and he is eating, for example, chocolate Neapolitan wafers. He loves eating those but he always offers everybody else at the table. He offers again after some time has passed. Miloš enjoys his Neapolitans, he enjoys them and he knows that others might enjoy them as well. Miloš is one, of a kind. They have labeled him a certain colorless shade on a spectrum of illness no one knows anything about. But we do, and Miloš knows even better, because he is teaching us. Chocolate Neapolitans, paper and pencil, a verse, a name-call, the essence of truth, a frightening probability. You don’t have to be afraid of Miloš, he will put you in a song, next to a cock or a cunt, it’s inevitable, you just have to stop running. If you run and show fear, he will sense it. He will do nothing to you except maybe sing about you more often. Sometimes it’s not easy to read his poetry and dread the following verse because with a fleeting glance you saw the outlines of your name. Your turn will come.

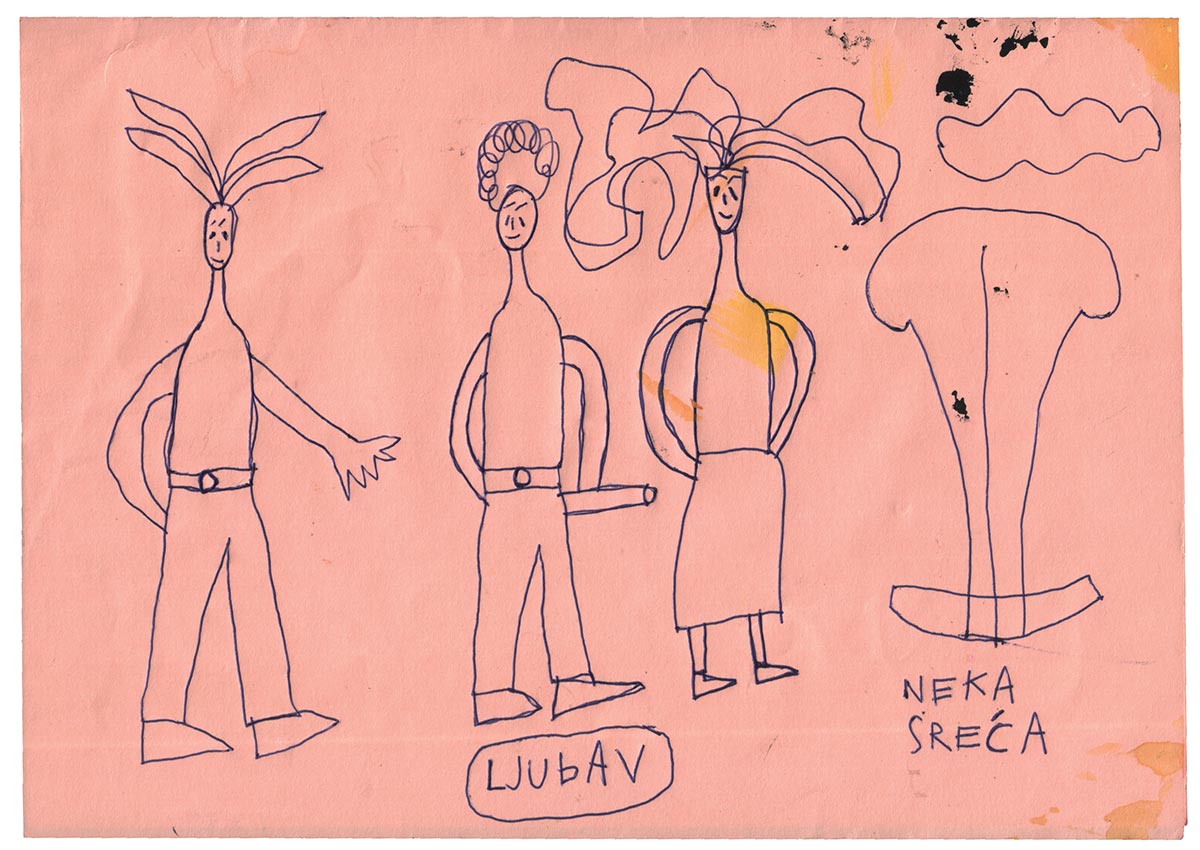

Miloš is always in love. His love is not an empty romance, like, for instance, Bata’s numerous relationships, which can sometimes last as long as the next girl that appears in his life. Bata is a romantic polygamist, while Miloš is the tall, dark stranger. His intentions are clear, a girl he talks to is never in doubt. Miloš knows what he wants, he doesn’t yet know how to get all that he wants, because he wants so much, he wants his apartment, he has no problem with having a job, he likes money but he doesn’t spend much, he is frustrated by the material world, which is why he talks about it so much; if it were up to him, he and his girlfriend would lay in bed in his or theirs, rented or inherited, or whatever kind of, apartment, they would never be looking at the ceiling at the same time, the alternating current of their calorie-burning and, for the occasion, accelerated metabolism, would shoot lightning bolts across the room, across the whole one-room apartment.

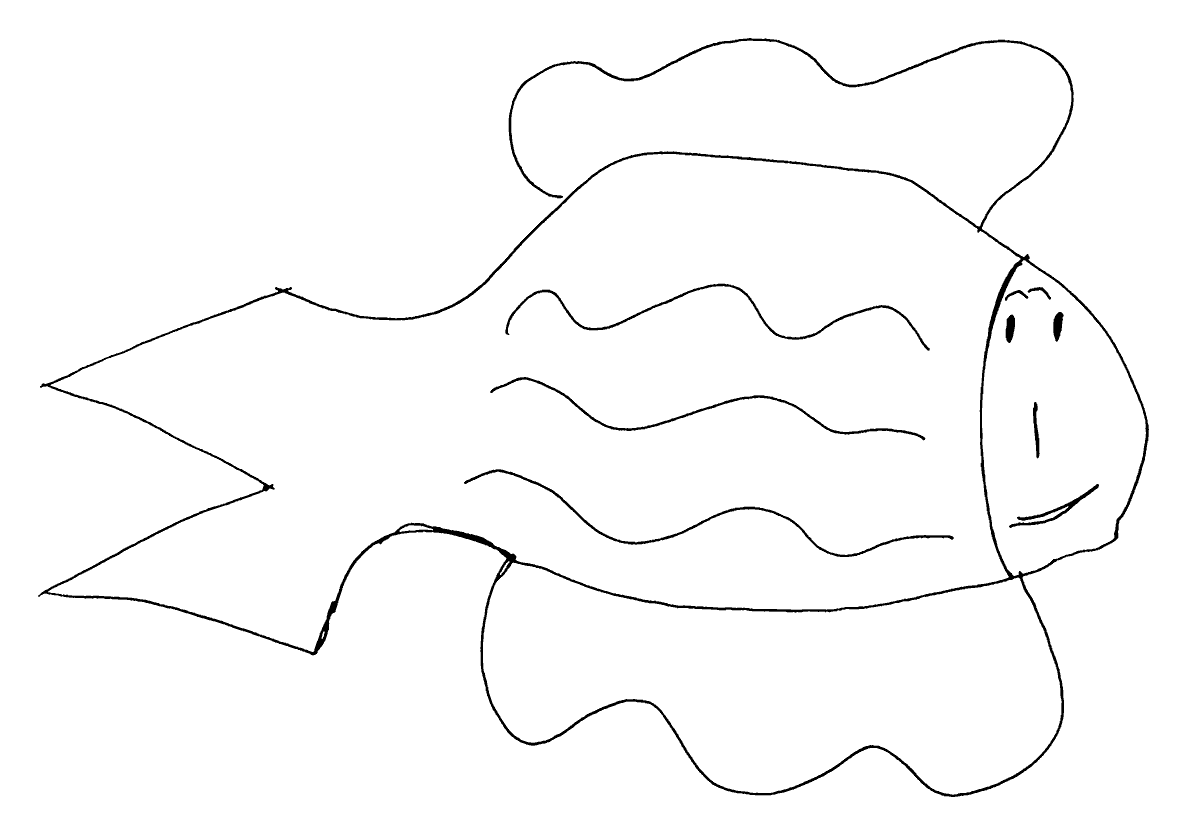

This is Miloš, he is a hunter. Ten thousand years ago, somewhere, I don’t know, he would have been an important member of the tribe. He would simply not be fucked with. He would leave imprints of his blood-colored hand on the walls, draw bulls, hunt deer; women would fight for a place next to him. I don’t know, maybe they would stone him out of the tribe, maybe even kill him. Either way. He would concede, because those guiding him, overseeing him, even friends with kind advice would always make him feel confused. How many times have I found myself in a situation where I stood in front of him filled with shame after generously giving him some meaningless advice? I could feel my ears burning with shame just standing there in front of him, this child, this man, this hunk, this creator, because that’s who he is. He was sent here. He can talk to them. We can’t see them.

Maybe, if only we could prick our ears some more, we might be able to hear who he was warring or fighting with. Maybe we are cowards, maybe we are the same ambivalent surroundings he has at home, and infidels are everywhere these days. Maybe, one day, the sky will close down, the icy wind will freeze everything in place, anything that moves will fall, stumbling, grimace-shaped icicles will shatter on the ground, enormous blue and green fire balls will rain from the sky, tailless egg-shaped meteors will shoot straight at our heads, we won’t lose consciousness and we will feel all this pain. Miloš will be there, ready, because he has waited for them, brave because he wasn’t afraid of them, strong because they are stronger, the sun rays will shine with astonishing intensity, yet pleasing to the eye, and through Miloš’s eyes, he will melt all that’s frozen, like he’s always done, with a gentle breath of freshness he will cool down our burning limbs, our bodies burning to a cinder, which is nothing new. And time will only tell that just this one man, this child, this boy, this youth, from our house, one of the Beatlsts, moderately correct, or sufficiently so, that he was right, despite the numbers, despite the ruthlessness of statistics, despite all the odds, and at the expense of the environment… although, I think that even after this victory, this Pyrrhic status quo, during a twilight of conflict, everybody worn-out, at the end of some fictitious battle, if they were to ask him, to reward him for saving them, for a sacrifice at the altar of humanity, what would you like Miloš? I think even then he would show dignity, and humility, the beauty of his expression, the irrelevance of the chosen weapon, he would wish for just a little, maybe half a kingdom, houses made of chocolate, the emperor’s daughter, the older one, and the younger one, and maybe only one room, a small room at the top of a golden castle, his own little kingdom. That is our Miloš. May those who know him greet him and kiss his hand, and may all his wishes come true, to get separated from this world, to receive half of Naples for one Neapolitan, chocolate-coated, hard on the outside, soft on the inside, that sometimes tastes like sugar and cocoa, and sometimes like real chocolate.

Radovan Popović